What is the coffee belt?

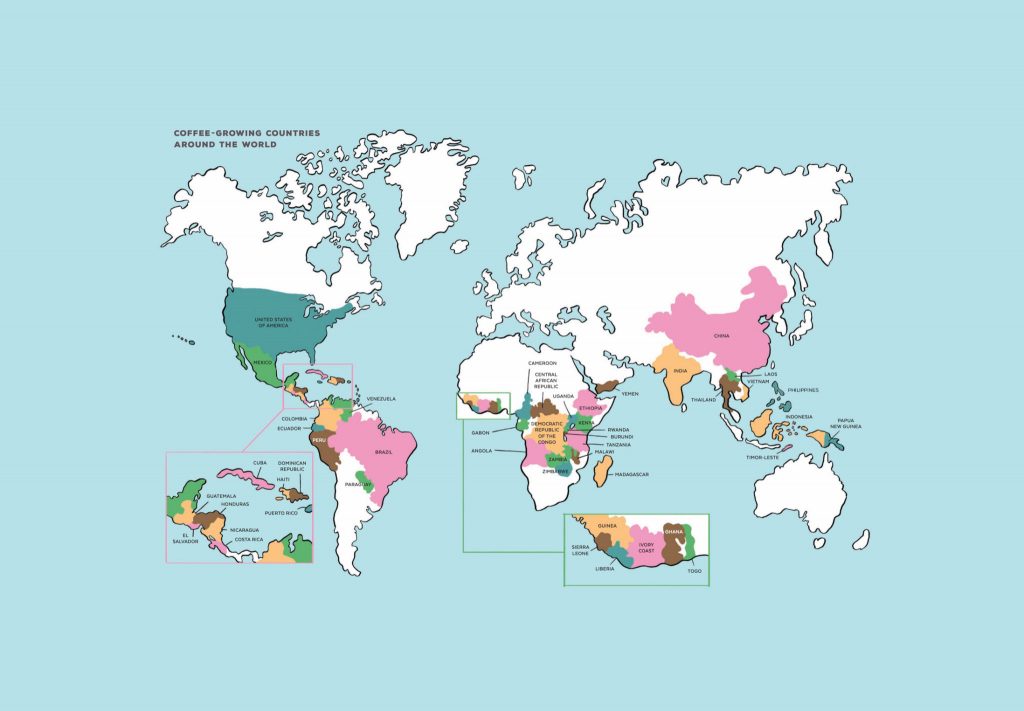

The coffee belt refers to the equatorial regions of the earth where coffee is most easily grown—between 25 degrees north of the equator and 30 degrees south, a range almost entirely overlapping the Tropics, according to the National Coffee Association. This region includes coffee-producing areas such as Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, the United States (California, Hawaii, Puerto Rico), Venezuela, China, India, Indonesia, Laos, Nepal, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Liberia, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Timor Leste, Trinidad and Tobago, Togo, Uganda, Yemen, Zimbabwe, and Zambia—to name a few.

(The coffee belt is not to be confused with this coffee belt buckle by Nicaragua’s Fincas Mierisch).

Why does coffee grow better in the coffee belt than elsewhere?

Just like growing the best plants for your garden zone at home, coffee has specific needs to thrive. These include mild temperatures, higher humidity, and rich soil, as well as, in some cases, altitude. For Arabica coffee, high, mountainous regions with the right balance of sun, clouds, and day/night temperature differences can furnish the ideal conditions for coffee to grow. Most of the coffee belt also has a rainy season (areas closer to the equator have more than one) which coffee plants also need. (Picky as they are, they also want a dry season, too.)

In countries like Ethiopia or Colombia, coffee is commonly grown at high elevations, upwards of 1800 meters, and high-grown coffee is typically considered to be of high quality for the effect such elevations have on flavor in the cup. Not all coffees in the coffee belt grow at high elevations, however, most notably Brazil, which grows a tremendous amount of the world’s coffees at much lower elevations than this. (For example, the first place coffee in Brazil’s 2020 Cup of Excellence was grown at only 850 meters above sea level.)

Robusta coffees grow more easily at lower elevations, and can tolerate sun and drought more easily than Arabica coffee plants.

(The coffee belt is not to be confused with this coffee belt buckle by Nicaragua’s Fincas Mierisch).

How did coffee come to be cultivated in the coffee belt?

Coffee’s commercial cultivation is believed to be traced back to Yemen, where beans from Ethiopia—widely considered coffee’s birthplace, and where coffee grows wild—were brought in or before the 15th century. Both countries, of course, lie within the coffee belt.

Does anything else grow in the coffee belt?

Plenty of wonderful things grow in the tropics, like bananas, avocados, and pineapples. But cacao—a plant some may say is coffee’s best friend?—grows along an almost identical swath of latitude. Only they call it the Cacao Belt!

Can coffee grow outside the coffee belt?

Hobby growers and coffee enthusiasts have grown coffee in more northerly and southerly climes than the coffee belt, but it simply isn’t practical to farm coffee on the scale needed to make production worthwhile outside of the coffee belt. This may change with climate change, as areas further from the equator become warmer and potentially more hospitable to coffee cultivation, but this is not a shift most of us are looking forward to.

How is climate change affecting the coffee belt?

The coffee belt is extremely susceptible to climate change and indeed is already seeing its effects, with temperatures higher and rainfalls less abundant in equatorial regions in the last several decades. Increases in heat—be they extreme or even slight—have a deleterious effect on farmable coffeelands, and what’s worse, these higher temperatures and lower rainfalls allow for the proliferation of threats to the coffee plants themselves, like coffee leaf rust disease and the coffee borer beetle. Though agricultural scientists are hard at work on more disease- and pest-resistant cultivars, it’s indisputable that climate change poses a serious threat to coffee farming as we know it. By 2050, climate scientists warn, the

0 comments